Pages

▼

Friday, January 24, 2020

Wednesday, January 22, 2020

#SayHerName #SilentFilmEdition Mabel Condon Birdwell

Mabel "Mimi" Condon was only 18 when she began writing for Chicago's film trade magazine "Motography." In that same year she not only wrote on the inner workings of Chicago's film censorship board and the process of turning a scenario into a film but also the "Sans Grease Paint and Wig" feature where her interactions with celebrities and actors were profiled. Where many other trade profiles had focused on the tabloid nature of Hollywood, Condon would continue throughout her writing career to highlight the actors' real lives as well as their relationships with their fans. When encountering William Russell for "Sans Grease Paint and Wig", she had insisted for him to take the single chair in his dressing room and Condon sat on the edge of his desk. Within months in 1912, she was promoted to associate editor of the whole journal.

In 1913, Motography opened an office in New York City and promoted Condon as its East Coast representative. They had justified their choice, describing her as "already known personally to most of the trade, and through her departments at Motography, to most of our readers." Condon had continued at Motography for two more years until leaving in June 1915. She moved to Los Angeles in 1915 and not only continued to write for film interviews and reviews, but also began to work as a press agent, became the The Dramatic Mirror's West Coast representative, and also created a committee to represent the Motion Picture Board of Trade activities in Southern California. Condon would also start to write screenplays, her best known scenario being "The Man Who Would Not Die."

Within a year of living in Los Angeles, The Mabel Condon Exchange was created as both a publicity agency and an employment exchange. Condon would help assist actors in finding roles and arranging their contracts, publicity, and finances in addition to selling scripts and story rights. The Moving Picture World would describe "the growth [as] phenomenal. ... A number of the prominent screen stars requested her to handle their publicity. The business took on such proportions that she was compelled to engage several assistants and open an office in Hollywood." (The Moving Picture World, Volume 29) The exchange represented both authors of the screen and stage as well as including an engagement department. From August to September 1916, The Mabel Condon Exchange handled over 800 photodramas through the play department and only 48 sold to the studios. Condon made sure to employ women, including former actresses Adelaide Woods, Nell Shipman, Anita Stewart, and Myrtle E. "M.E.M" Gisbone, Kalem Company's West Coast manager.

Condon had a son with publicist Russell Juarez Birdwell in 1924 and between then and the mid-1930, she had closed the exchange entirely to raise her children full-time. In 1936, she had taken a trip to Asia for four months where she had written a book entitled "Housewife Abroad" which ended up released at the same time as the Mabel Condon Agency opened. The only two branches were set in Beverly Hills and Singapore. Birdwell would frequently rely on her connections and even took advice from her after being hired as David O. Selznick's head of publicity and even when he opened his own advertising firm in Los Angeles. Condon would maintain the relationships with his clients while Birdwell spent most of his time on the East Coast. She officially became Russell Birdwell and Associates's public relations executive in 1944, making sure to remove her married name from the original draft of this release believing her name would still carry some weight.

Heart disease eventually kept her from her work until dying from a heart attack in 1965. A New York Times obituary described her as "a former writer and literary agent." The Los Angeles Times identified Condon in her own obituary as "wife of publicist Russell Birdwell."

Cool Links to Check Out

Monday, January 20, 2020

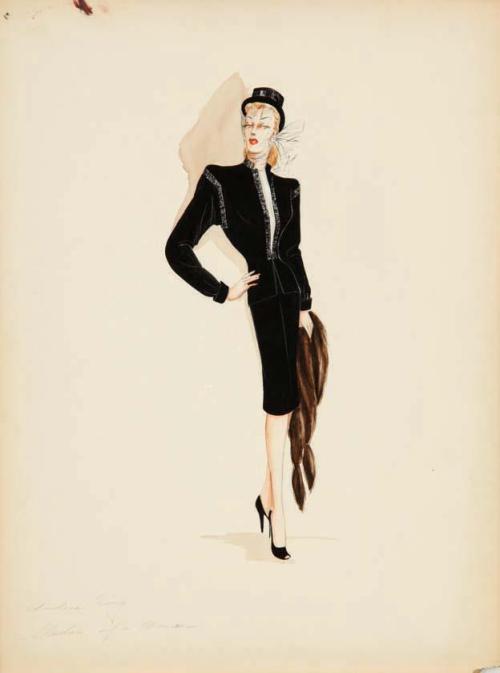

#MaleFashionDesigners #FashionSpotlight Milo Anderson

Constance Bennett gave a young fashion designer Milo Anderson a tip that had stayed with him throughout his three-decade career. "It's not what you put on a costume, it's what you take off that counts." His parents had moved to Los Angeles when Milo was 8 and had worked at Western Costume in high school. Anderson even got to do some designing including for Constance Bennett in "Common Clay." (1930) After graduating, he attended and graduated the University of California.

Milo

He left Warner Brothers in favor of joining Robert Muir and Associates as an interior designer and often taught classes at the Sacramento Art Centre on costume design. Milo passed away of emphysema on November 10th, 1984.

|

| Andrea King in "Shadow of a Woman" (1946) |

|

| Irene Dunne in "Life with Father" (1947) |

|

| Elissa Landi |

Tuesday, January 14, 2020

Make This!: Tallulah Bankhead and Lillian Hellman Season of "Feud"

Communist stage and screen writer Lillian Hellman considered herself "a most casual member" in later years. But in December 1936, her play "Days to Come" closed on Broadway just after seven performances, Communist publications criticized her failure to take sides between the factory owners and its workers instead of representing both sides as valid. She had officially joined the party two years later. Hellman's personal favorite play she had written, "The Little Foxes," opened on February 13, 1939 and this time, it was considered a hit running for 410 performances until February 3rd, 1940. The company then toured for a whole year after.

After the USSR invaded Finland on November 30, 1939, many stars from John Barrymore to Edward G. Robinson offered to assist in Finnish relief. "Foxes"'s lead, Tallulah Bankhead was no exception. She

"Producers are

Hellman started telling everyone that she had an interview with the New Yorker claiming that it was

|

| Elisabeth Moss as Tallulah Bankhead |

| Grace Gummer as Lillian Hellman |

|

| Ebon Moss-Bacharach as Herman Shumlin |

Friday, January 10, 2020

Wednesday, January 8, 2020

#WomenDoingAwesomeThingsWednesday Teresa Wright's Bathing Suit Clause

Teresa Wright was a year into her two-year contract playing Mary Skinner in the

The "bathing suit" clause went as follows:

"The aforementioned Teresa Wright shall not be required to pose for photographs in a bathing suit unless she is in the water. Neither may she be photographed running on the beach with her hair flying in the wind. Nor may she pose in any of the following situations: In shorts, playing with a cocker spaniel; digging in a garden; whipping up a meal; attired in firecrackers and holding skyrockets for the Fourth of July; looking

Monday, January 6, 2020

#MaleFashionDesigners #FashionSpotlight Marcel Vertes

Marcel Vertes was among of the many who escaped the Nazi invasion of Europe. For Vertes, he was able to escape the invasion of Paris by two days. He and his wife was not strangers to New York.

Before the move, Vertes was familiar with

|

| Rita Hayworth in "Tonight and Every Night" (1945) |

|

| The Mikado (1939) |

|

| June Duprez in "Thief of Bagdad" (1940) |