History

Prana-Film producer Albin Grau ignored the possible copyright lawsuit on his hands when he pressed forward with his "Dracula" adaptation "Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens" (1922). Germany was already one of the official signatories to the 1886 Berne Convention, which ensures that "every production in the literary, scientific and artistic domain, whatever the mode or form of its expression" must be protected. Bram Stoker's widow Florence Balcomb would not sell him the rights and the changes screenwriter Henrik Galeen made to the script were not enough even though the Dracula name was still included on some of the early versions. Stoker's estate filed suit, claiming the film an infringement even after the film debuted on March 4th, 1922 to successful reviews.

Grau was forced to declare bankruptcy and close his newly formed production company. All German copies of "Nosferatu" were promptly eradicated and destroyed although a few "were already in circulation throughout Europe and the British court was unable to track them down and destroy them (the surviving prints wound up in France, out of the jurisdiction of the British legal system)." (THE BOOTLEG FILES: NOSFERATU | Film Threat) It was easy for Stoker's estate to get a hold of the British and German copies thanks to cameraman Fritz Wagner Arno having shot with only one camera to save on costs.

Only one copy was sent to the U.S. and it helped that "Dracula" was already in the public domain largely in part to an error in the copyright notice. The U.S. was also not a signatory of the Berne Convention until 1989. But "Nosferatu" would premiere seven years later on June 3, 1929 at Brooklyn's Film Guild Cinema. The April 1929 issue of Theatre Guild Magazine would run an ad for the film calling it "inspired by from Dracula... a symphony in gray... moods macabre and mordant... a powerful psychopathic study of bloodlust..." (Nosferatu: History and Home Video Guide, Part 2 - Brenton Film)

Mordaunt Hall of The New York Times called "Nosferatu" "not especially stirring. It is the sort of the thing one could watch at midnight without its having much effect upon one's slumbering hours. [...] The backgrounds are often quite effective, but most if it seems like cardboard puppets doing all they can to be horrible on papiermache settings. [...] It is a production that is rather more of a soporific than a thriller. Max Schreck's movements as Nosferatu are too deliberate to be lifelike." Variety lauded F.W. Murnau as "a master artisan demonstrating not only a knowledge of the subtler side of directing but photography" and Max Schreck "an able pantomimist and works clocklike, his makeup suggesting everything that's goose pimply."

The American distributor, Film Arts Guild went out of business shortly after the release, leaving "Nosferatu" doomed to public domain status.

Carl Theodor Dreyer had a critical success but a financial disaster in "La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc" (1928), and the breach of contract law suit against his production company Société Générale de Film wasn't helping much either after they wrongly cut the film as to not offend Catholic viewers without his consent. But Dreyer had one more film to be financed, but it ended up dropped which led to his wanting to work outside of the studio system. But French film studios were technologically behind with the coming of sound films and Dreyer chose to go to a more progressively learned England to study sound film.

While in England, he met fellow Dane, writer Christen Jul. He also read over thirty mystery stories while in London, finding "a number of re-occuring elements including doors opening mysteriously and door handles moving with no one knowing why." Dreyer called on Jul's talents and together, they decided to write a film about vampires which Dreyer considered "fashionable things at the time" and that "we can jolly well make this stuff too." He and Jul drew elements from J. Sheridan Le Fanu's short story collection In a Glass Darkly, specifically the live burial from "The Room in the Dragon Volant" and female vampires from "Carmilla." But a title was a little more difficult to generate, Dreyer possibly titling it "Destiny" then "Shadows into Hell."

Upon returning back to France for casting, Dreyer met Baron Nicolas de Gunzberg, a Dutch aristocrat, through artist and writer Valentine Hugo. Gunzberg agreed to finance "Vampyr" in return for playing the lead role, Allan Grey when the original backing fell through. He would be credited under the psuedonym Julian West when his family argued against his becoming an actor. Dreyer would also hire many of his crew from "La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc" including cinematographer Rudolph Maté and art director Hermann Warm.

It was up to Dreyer's assistant to provide some scouting which Dreyer and Maté also contributed in. His instructions to his assistant was to find "a factory in ruins, a chopped up phantom, worthy of the imagination of Edgar Allan Poe. Somewhere in Paris. We can't travel far." While finding a suitable mire for the doctor to die in, the crew found a mill where there were white shadows moving around the windows and doors. The film's ending changed from the doctor dying in a swamp to suffocating under milled flour. Everything was shot on location, Dreyer believing by "lending the dream-like ghost world of the film as well as allowing them to save money by not having to rent studio space."

Production started in the spring of 1930 at Courtempierre France and lasted over a year. Other locations included Senlis and Montargis outside of Paris. The scenes in the chateau were shot in April and May 1930 which also housed cast and crew during filming. Also being financed by the German studio Tobis-Klangfilm, Dreyer shot each scene in German, French and English. "The Baron de Gunzberg recalls: "Each scene was shot three times for the French, English and German versions whenever there was any dialogue involved. It was shot silent with all of us mouthing the words. The sound was put in later at the UFA studios in Berlin, as they had the best sound equipment at that time."" (Vampyr (1932) - Turner Classic Movies) Gunzberg would also recount that Dreyer insisted filming exterior scenes at dawn because "the light gave the best effect of sundown."

"Vampyr"'s style had changed from what Dreyer described as a "heavy style" but changed when Maté showed him a shot that came out fuzzy and blurred. "We had begun shooting on the film," Dreyer explains, "- starting with the opening scene - and after one of the first screenings of the rushes we noticed that one of the takes was gray. We wondered why, until we realized a false light had been projected on to the lens. We thought about that take, the producer, Rudolph Mate and I, in relation to the style we were looking for. Finally, we decided that all we had to do was deliberately repeat the accident. So after that, for each take we arranged a false light by directing a spotlight hung with a black cloth on the lens." Many other shots were inspired by Spanish Romantic painter Francisco Goya and the sounds of animals in the film were created by professional imitators.

Filming was completed in the middle of 1931 and premiered in Berlin on May 6, 1932 when the studio wanted America's "Dracula" and "Frankenstein" (1931) to be released first. The audience booed which led Dreyer to cut several more scenes after the first showing. When it premiered in Paris in September at a new cinema on the Boulevard Raspail, "New York Times reporter Herbert L. Matthews wrote, "It is a hallucinating film which either held the spectators spellbound as in a long nightmare or else moved them to hysterical laughter."" (THE BOOTLEG FILES; VAMPYR | Film Threat) When Vienna audiences were denied their money back during the Italian premiere, a riot broke out that led to the police having to restore order with nightsticks. Dreyer would not attend "Vampyr"'s premiere in Copenhagen in March 1933. The film would premiere in the U.S. on August 14, 1934 under the title "Not Against the Flesh." The film was a financial failure.

Reviews were just as brutal. "Whatever you think of the director Charles [sic] Theodor Dreyer," a critic from the New York Times wrote, "there's no denying that he is 'different.' He does things that make people talk about him. You may find his films ridiculous--but you won't forget them. Although in many ways [Vampyr] was one of the worst films I have ever attended, there were some scenes in it that gripped with brutal directness."

When Dreyer asked about the intention of the film at the Berlin premiere, he replied that he "had not any particular intention. I just wanted to make a film different from all other films. I wanted, if you will, to break new ground for cinema. That is all. And do you think this intention has succeeded? Yes, I have broken new ground."

You Have Hurt Yourself ... Your Precious Blood! The Blood! The Blood!

In 1838, realtor employee Thomas Hutter is sent to a castle in the Carpathian Mountains where he sells a Wisborg property to the strange and rat-like Count Orlok. Despite the warnings he receives on his way there, Hutter is continually creeped out by Orlok's appearance and demeanor towards his accidentally cutting his thumb. The fact that Orlok is also fascinated with his wife, Ellen, doesn't help much either. Within days, he is abandoned at the ruins and the strange Count is on his way to his new home in Wisborg. Hutter ends up making his escape through a tall window and is knocked unconscious, then taken to a nearby hospital.

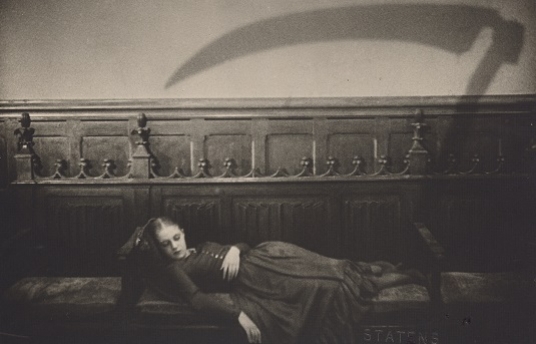

Ellen has been prone to trance-like states since Hutter's departure and continues to get worse under the watchful eye of family friends. But the whole town ends up victim to a plague associated to a sudden influx of rats since the schooner carrying Orlok docks. Hutter recovers from his injuries and is on his way home where people are dying left and right and doctors struggle to understand and cure the plague.

With Hutter home, Ellen recovers enough to go through his things and discovers a book of vampires he is given while on his travels. Determined to save her husband, Ellen takes matters into her own hands.

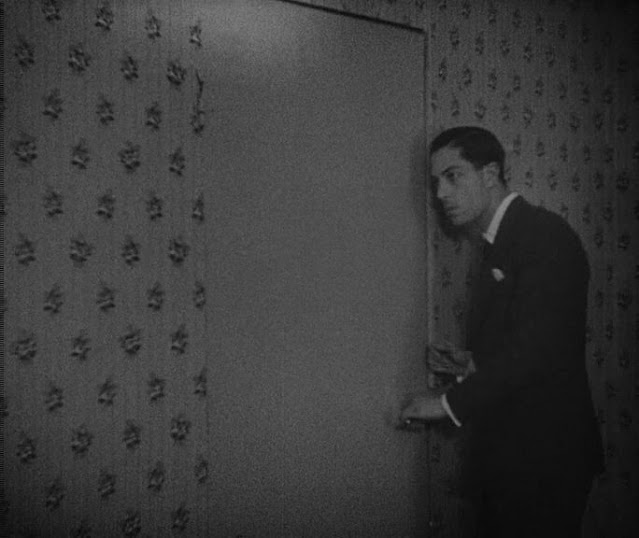

Allan Gray is traveling to particularly nowhere when he arrives at a Courtempierre inn. Once he settles in for the evening, he is visited by the apparition of an old man who gives him a square package which is wrapped with paper and signed "to be opened upon my death." As if Gray was under a spell, he takes it and leaves the inn. Shadows guide him to a castle; Gray also discovering an old woman and the village doctor as he is taken from the castle to a manor.

When he looks around the manor, he finds that same old man who gave him the package murdered by an unseen assailant through a window. Gray rushes towards him, but neither he or the manor's servants can save him. The servants insist he stay the night and Gray meets the youngest sister, Gisele. The oldest, Leone, is ill despite the both of them discovering her walking outside just as Gisele started talking about her. They rush out to bring her back in, but find Leone unconscious and bitten. This seems to prompt Gray's memory and goes into his things for the package. The package contains a book entitled "Vampyrs" explaining what they are and how they are to be killed.

The old man Gray met on his way to the manor is revealed to be the village doctor comes to the manor the next day to check on Leone. When the doctor insists she needs a blood transfusion, Gray ends up offering his services. He wakes up in a daze but realizes danger. Running into Leone's room, he finds the doctor attempting to poison the oldest daughter and the youngest is nowhere to be found. He chases the doctor back to the castle and rescues Gisele. But the male servant of the manor has found Gray's book and is ready to take matters into his own hands with or without Gray's help.

Death Match

Between "Nosferatu" and "Vampyr," it's a total toss-up. The both of them are beautiful films between Murnau's metronome-directed direction of his actors and "Vampyr"'s use of mixing silent film with sound and passive surrealism. But when you really look at the differences, there is a distinct separation between the two films: bow does a filmmaker make a surrealistic horror film to watch versus a surrealistic horror film that can be felt.

"I wanted to create a waking dream on screen," Dreyer once explained about "Vampyr," "and show that horror is not to be found in the things around us but in our own subconscious." He achieves this through his often described dreamer male lead, Allan Gray, who wanders from adventure to adventure and from continuity error to another. After saving Gisele from the doctor, it's as if an episodic "Allan Gray Adventure" skips its end credit sequence and the character finds himself walking into frame in a graveyard where the servant is digging up Marguerite Chopin's grave knowing she is the vampire at fault for Leone's illness. The editing is clipped from adventure to adventure and yet that inconsistency is the point in a surreal "waking dream" -- it's much more psychologically titillating that doesn't necessarily frightens but heightens and that's something, I hate to say, "Nosferatu" somewhat lacks.

"Nosferatu" has its roots in the occult, Albin Grau already being an established member of the Fraternis Saturni under the name of Master Pacitius. Grau and Enrico Dieckmann created Prana Film with the plan to produce mostly supernatural and occult-inspired films whose symbols are often displayed throughout the film which grounds the film mostly in a Christianized "other," making it "scary" yet rooted for '30s viewers.

While nightmarish and beautifully moody, "Nosferatu" is not entirely in the realm of the surreal but the fantastical being the unofficial adaptation of "Dracula." We are watching than feeling and reacting to our observing this world of horror in front of us that has a rat plague and a vampirish aristocratic Count and a mad boss of a realty company with an affinity for bugs and spiders. Its photography will always be stunning and the acting purposefully slow and off-kilter, but "Nosferatu" will always be a pillar in the Expressionist genre no matter what kind of viewer you are.

It really just matters of what kind of horror movie you're in the mood for for the night.

No comments:

Post a Comment